This post originally featured on the Castletown House blog

By Catherine Bergin-Victory

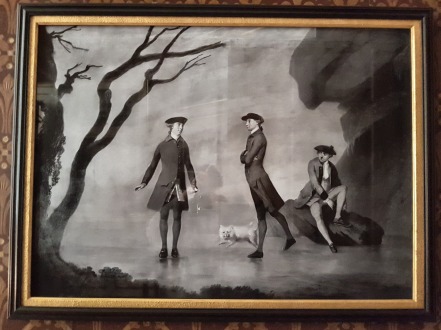

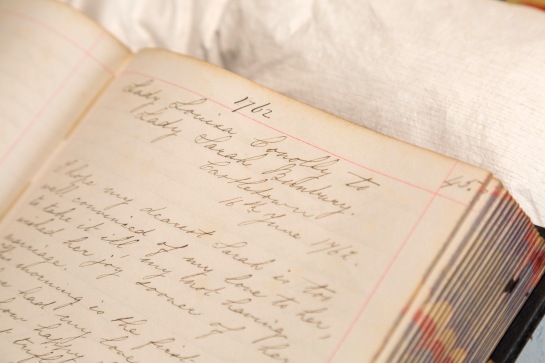

‘My dear soul what possessed you?’ a seemingly exasperated Lady Louisa asked her sister Lady Sarah in a letter dated 26 January 1762. Lady Sarah, sister of Castletown’s Lady Louisa Conolly (née Lennox) is, arguably, one of the most colourful characters associated with the house. It is fitting that we mark her today, considering not only is this St Valentine’s Day and she had a most colourful romantic life but also this day marks her birthday. Lady Sarah was born 14th February 1745.

So what did Lady Sarah do that provoked a reprimand from her older sister? Prepare yourself… Lady Sarah engaged in a flirtation with a gentleman, a Sir Thomas Charles Bunbury! Unfortunately, there are no details in the letter but it is clear that Lady Sarah was too flirtatious and may have led Bunbury to believe she does not ‘think anything serious’ (about marriage?). For an 18th century lady, that could have been a deadly faux pas! However, the letter end with some consolation, ever the big sister Lady Louisa signs off hoping that Lady Sarah’s ‘manner to him for the future will regain him’.

Perhaps, it was no wonder Lady Louisa was keen to see her younger sister married. Lady Sarah, just shy of 17 years at the time of this letter, had already been jilted by George III, courted by several suitors and turned down at least one proposal. As a young 18th century woman, Lady Sarah was expected to marry, and marry well. Anyone who has ever gone through the first volume of Lady Louisa’s letters to Lady Sarah (available at the OPW-Maynooth University Archive and Research Centre at Castletown), will encounter Lady Sarah’s love interests, suitors and her disappointments.

Yet just over a month later, Lady Louisa would write quite a different style of letter, this time enthusiastically congratulating Lady Sarah on her engagement.

Within four months of the first reference to Bunbury, and within one month of serious references to him as a potential husband, Lady Sarah was now an engaged woman. In this romantic of months, and in the same month of her birthday, had Lady Sarah truly met her match?

To find out, we will hold off until 29th February, choosing this date (it being a leap year!) to turn our attention to marriage!

The letters of Lady Louisa Conolly are available for consultation by appointment at the OPW-Maynooth University Archive and Research Centre.